Beginners Guide to Apache HTTPD

Introduction To Apache HTTPD

Apache HTTPD is one of the most used web servers on the Internet. A web server is a daemon that speaks the http(s) protocol, a text-based protocol for sending and receiving objects over a network connection. The http protocol is sent over the wire in clear text, using port 80/TCP by default (though other ports can be used). There is also a TLS/SSL encrypted version of the protocol called https that uses port 443/TCP by default.

A basic http exchange has the client connecting to the server, and then requesting a resource using the GET command. Other commands like HEAD and POST exist, allowing clients to request just metadata for a resource, or send the server more information.

The following is an extract from a short http exchange:

GET /hello.html HTTP/1.1

Host: webapp0.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:24.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/24.0

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: keep-alive

Cache-Control: max-age=0

The client starts by requesting a resource (the GET command), and then follows up with some extra headers, telling the server what types of encoding it can accept, what language it would prefer, etc.The request is ended with an empty line.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Tue, 27 May 2014 09:57:40 GMT

Server: Apache/2.4.6 (Red Hat) OpenSSL/1.0.1e-fips mod_wsgi/3.4 Python/2.7.5

Content-Length: 12

Keep-Alive: timeout=5, max=82

Connection: Keep-Alive

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=UTF-8

Hello World!

The server then replies with a status code (HTTP/1.1 200 OK), followed by a list of headers. The Content-Type header is a mandatory one, telling the client what type of content is being sent. After the headers are done, the server sends an empty line, followed by the requested content. The length of this content must match the length indicated in the Content-Length header.

While the http protocol seems easy at first, implementing all of the protocol—along with security measures, support for clients not adhering fully to the standard, and support for dynamically generated pages—is not an easy task. That is why most application developers do not write their own web servers, but instead write their applications to be run behind a web server like Apache HTTPD.

About Apache HTTPD

Apache HTTPD, sometimes just called “Apache” or httpd, implements a fully configurable and extendable web server with full http support. The functionality of httpd can be extended with modules, small pieces of code that plug into the main web server framework and extend its functionality.

On CentOS/RHEL 7 Apache HTTPD is provided in the httpd package. The web-server package group will install not only the httpd package itself but also the httpd-manual package. Once httpd-manual is installed, and the httpd.service service is started, the full Apache HTTPD manual is available on http://localhost/manual. This manual has a complete reference of all the configuration directives for httpd, along with examples. This makes it an invaluable resource while configuring httpd.

CentOS/RHEL 7 also ships an environment group called web-server-environment. This environment group pulls in the web-server group by default, but has a number of other groups, like backup tool and database clients, marked as optional. A default dependency of the httpd package is the httpd-tools package. This package includes tools to manipulate password maps and databases, tools to resolve IP addresses in log files to hostnames, and a tool (ab) to benchmark and stress-test web servers.

Basic Apache Httpd Configuration

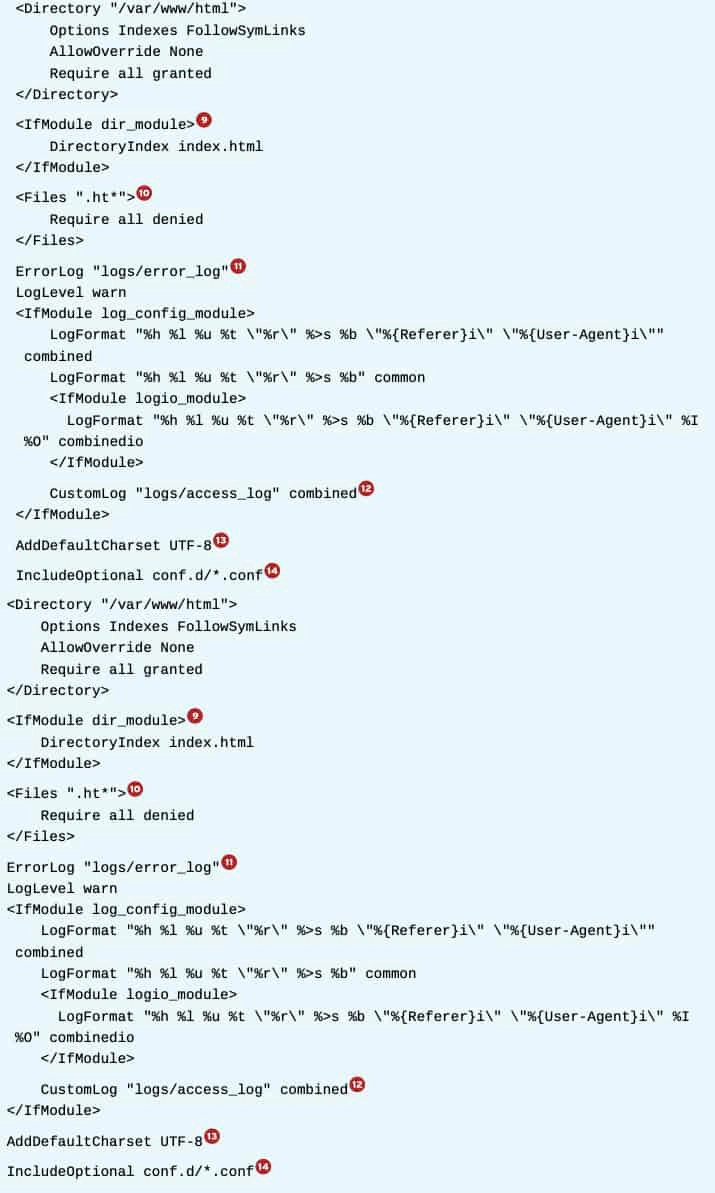

After installing the web-server package group, or the httpd package, a default configuration is written to /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf. This configuration serves out the contents of /var/www/html for requests coming in to any hostname over plain http.

The basic syntax of the httpd.conf is comprised of two parts: Key Value configuration directives, and HTML-like <Blockname parameter> blocks with other configuration directives embedded in them. Key/value pairs outside of a block affect the entire server configuration, while directives inside a block typically only apply to a part of the configuration indicated by the block, or when the requirement set by the block is met.

1. This directive specifies where httpd will look for any files referenced in the configuration files with a relative path name.

2. This directive tells httpd to start listening on port 80/TCP on all interfaces. To only listen on select interfaces, the syntax “Listen 1.2.3.4:80” can be used for IPv4 or “Listen [2001:db8::1]:80” for IPv6.

Note: Multiple listen directives are allowed, but overlapping listen directives will result in a fatal error, preventing httpd from starting.

3. This directive includes other files, as if they were inserted into the configuration file in place of the Include statement. When multiple files are specified, they will be sorted by filename in alphanumeric order before being included. Filenames can either be absolute, or relative to ServerRoot, and include wildcards such as *.

4 and 5. These two directives specify the user and group the httpd daemon should run as. httpd is always started as root, but once all actions that need root privileges have been performed—for example, binding to a port number under 1024—privileges will be dropped and execution is continued as a nonprivileged user. This is a security measure.

6. Some error pages generated by httpd can include a link where users can report a problem. Setting this directive to a valid email address will make the webmaster easier to contact for users. Leaving this setting at the default of root@localhost is not recommended.

7. A <Directory> block sets configuration directives for the specified directory, and all descendent directories.

Common directives inside a ****block include the following:

- AllowOverride None: .htaccess files will not be consulted for per-directory configuration settings. Setting this to any other setting will have a performance penalty, as well as the possible security ramifications.

- Require All Denied: httpd will refuse to serve content out of this directory, returning a HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden error when requested by a client.

- Require All Granted: Allow access to this directory. Setting this on a directory outside of the normal content tree can have security implications.

- Options [[+|-]OPTIONS]…: Turn on (or off) certain options for a directory. For example, the Indexes option will show a directory listing if a directory is requested and no index.html file exists in that directory.

8. This setting determines where httpd will search for requested files. It is important that the directory specified here is both readable by httpd (both regular permissions and SELinux), and that a corresponding <Directory> block has been declared to allow access.

9. This block only applies its contents if the specified extension module is loaded. In this case, the dir_module is loaded, so the DirectoryIndex directive can be used to specify what file should be used when a directory is requested.

10. A <Files> block works just as a <Directory> block, but here options for individual (wildcarded) files is used. In this case, the block prevents httpd from serving out any security-sensitive files like .htaccess and .htpasswd.

11. This specifies to what file httpd should log any errors it encounters. Since this is a relative pathname, it will be prepended with the ServerRoot directive. In a default configuration, / etc/httpd/logs is a symbolic link to /var/log/httpd/.

12. The CustomLog directive takes two parameters: a file to log to, and a log format defined with the LogFormat directive. Using these directives, administrators can log exactly the information they need or want. Most log parsing tools will assume that the default combined format is used.

13. This setting adds a charset part to the Content-Type header for text/plain and text/ html resources. This can be disabled with AddDefaultCharset Off.

14. This works the same as a regular include, but if no files are found, no error is generated.

Starting Apache HTTPD

httpd can be started from the httpd.service systemd unit.

# systemctl enable httpd.service

# systemctl start httpd.service

Once httpd is started, status information can be requested with systemctl status -l httpd.service. If httpd has failed to start for any reason, this output will typically give a clear indication of why httpd failed to start.

Network Security

firewalld has two predefined services for httpd. The http service opens port 80/TCP, and the https service opens port 443/TCP.

# firewall-cmd --permanent --add-service=http --add-service=https

# firewall-cmd --reload

In a default configuration, SELinux only allows httpd to bind to a specific set of ports. This full list can be requested with the command semanage port -l | grep ‘^http_’. For a full overview of the allowed port contexts, and their intended usage, consult the httpd_selinux(8) man page from the selinux-policy-devel package.

Using an alternate document root

Content does not need to be served out of /var/www/html, but when changing the DocumentRoot setting, a number of other changes must be made as well:

- File system permissions: Any new DocumentRoot must be readable by the apache user or the apache group. In most cases, the DocumentRoot should never be writable by the apache user or group.

- SELinux: The default SELinux policy is restrictive as to what contexts can be read by httpd. The default context for web server content is httpd_sys_content_t. Rules are already in place to relabel /srv/*/www/ with this context as well. To serve content from outside of these standard locations, a new context rule must be added with semanage.

# semanage fcontext -a -t httpd_sys_content_t '/new/ location(/.*)?'

Consult the httpd_selinux(8) man page from the selinux-policy-devel package for additional allowed file contexts and their intended usage.

Allowing write access to a DocumentRoot

In a default configuration only root has write access to the standard DocumentRoot. To allow web developers to write into the DocumentRoot, a number of approaches can be taken.

1. Set a (default) ACL for the web developers on the DocumentRoot. For example, if all web developers are part of the webmasters group, and /var/www/html is used as the DocumentRoot, the following commands will give them write access:

# setfacl -R -m g:webmasters:rwX /var/www/html# setfacl -R -m d:g:webmasters:rwx /var/www/html

Note: The uppercase X bit sets the executeable bit only on directories instead of directories and regular files. This is especially relevant when done in conjunction with a recursive action on a directory tree.

2. Create the new DocumentRoot owned by the webmasters group, the SGID bit set.

# mkdir -p -m 2775 /new/docroot

# chgrp webmasters /new/docroot

3. A combination of the previous, with the other permissions closed off, and an ACL added for the apache group.